ART AS SPIRITUAL FOOD

September 25, 2015

copyright Thomas Kadmon

Through the prism of : films on Mexican & Cuban artists

Recent trending news has included the Pope’s visit to Cuba and the USA, and the restoring of diplomatic relations between those two countries. The communist threat of Fidel Castro’s regime - the target of a chronic embargo - was also a place from which thousands of people attempted to defect to the more liberal and, in some respects, creative atmosphere of the United States. One was a trumpeter by the name of Arturo Sandoval, the subject of the the biographical movie For Love or Country (2000). It is therefore mildly reminiscent of the recently-discussed Mao’s Last Dancer.

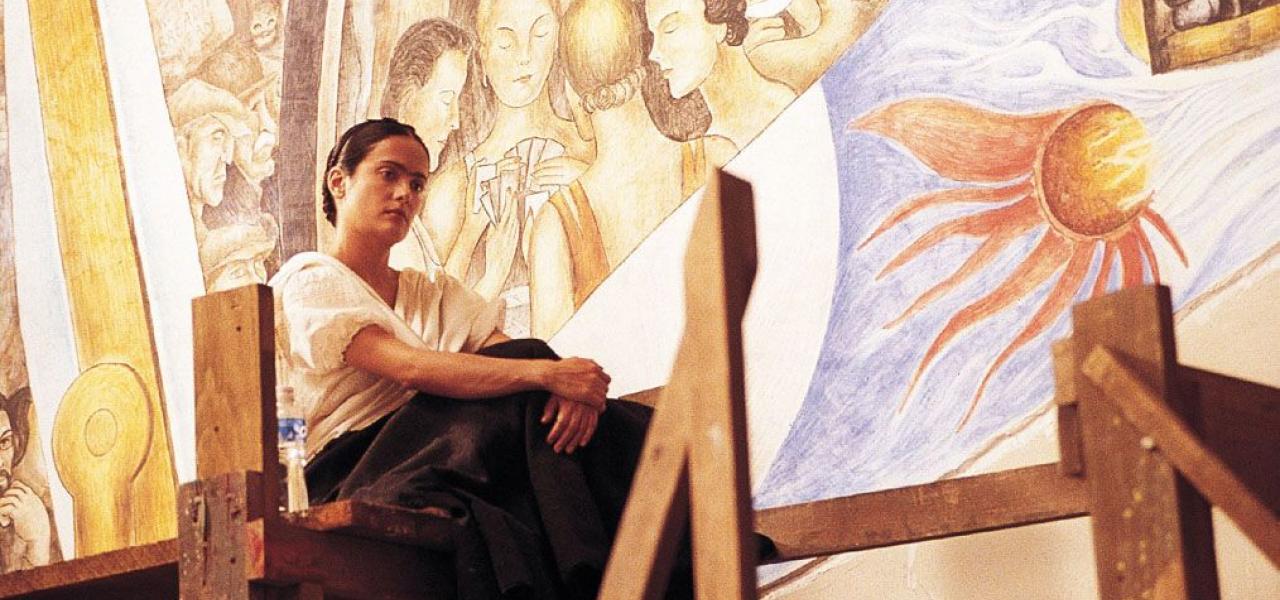

Sandoval’s musical creativity demanded freedom from the trammels of a communist regime, whereas Frida (2002) tells the story of the Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo, whose creativity was nourished by communism. Frida and husband, Diego Rivera, Mexico’s most famous artists, flouted bourgeouis convention : he drawing thematic inspiration from socialist revolution; she transmuting the pain of crippling injury into haunting and sometimes surreal pictures inspired by her personal experience. Although Arturo Sandoval is in love with a the communist, Marianella, to him, the creed means only pedestrian, state-sanctioned music and no personal compositions in his favourite jazz genre - associated with the sound of the United States and the work of the great Dizzy Gillespie, who was a trumpeting mentor to Arturo, as to Miles Davis.

The lead characters of For Love or Country and Frida, are played with deep spiritual sympathico by Andy Garcia and Salma Hayek respectively. Andy Garcia also had a hand in production - obviously a fan of Arturo’s music, which is a big drawcard of that particular film. For Arturo, home was a dream to be realised as not-Cuba. For Frida, home was that intense Blue House in Mexico - it could only be a painter’s house! Safety and creative freedomwere in that Blue House; as was independent proximity to the epic muralist Diego, that most unfaithful of lovers. Eventually Diego drove her into the arms of Trotsky who was granted political asylum in Mexico. Even for Trotsky, the Blue House meant safety and his last refreshment. Having left that sanctuary, he was met with a Stalin-sent icepick in the back of the head.

The Trotsky affair was a turning point in Diego’s and Frida’s relationship, and in the history of the communist movement. The prophet of international socialism was about to be eclipsed by the Soviet tyrant who sought a steel grip on his country alone. For a zenith moment though, that prophet was reinvigorated by the artistic spirit of Frida on the Aztec Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan. The other interfaith high point - a poignant ideological clash included by the director - was Diego’s refusal to accommodate Nelson Rockefeller’s scruple to have Lenin removed from a commissioned mural. “It’s my mural!” exclaimed Rivera. “On my wall!” returned Rockefeller, scion of the great dynasty of capitalism.

You could enjoy Frida’s film for the paintings, and Arturo’s for the music alone. An interfaith awareness adds another dimension. For the twentieth century artist or intellectual, ideological struggle is often a proxy for interfaith conflict. Arturo watched his dad, a brilliant mechanic, reduced by the regime to a non-enterprising domino player. His conclusion was that one’s gifts could not breath in a cultural atmosphere that stifled difference of opinion and self-employment. The torture of leading a double life to avoid persecution was painstakingly laid bare at the American embassy through which he sought to defect. Publicly, he was a member of the Communist Party; privately he harboured an American sense of life.

Curiously, America had failed to keep alive the rhythms of Dizzy Gillespie’s African heritage, whereas the dancers in the back streets of Cuba had succeeded.