ART AS SPIRITUAL FOOD

Through the prism of : the film “Gandhi”.

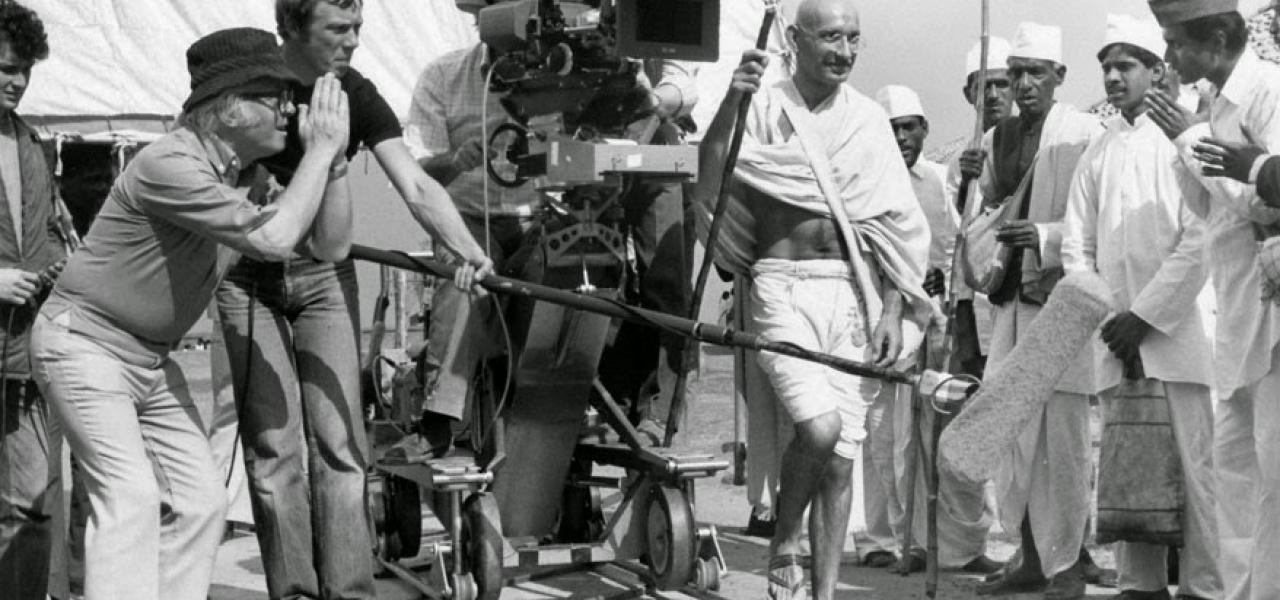

The 1982 Richard Attenborough film, “Gandhi”, about the Mahatma who helped India win its independence from the British Empire, was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, and won Best Film, Best Director and Best Actor (Ben Kingsley). So it is well worth a watch, to say the least. The film masterfully creates an ambience which excites spiritual aspirations in the viewer. When I first watched it as a uni student, I remember emerging exhilirated from the auditorium, with an expanded insight into what a commitment to truth in action might achieve.

This post reflects on three motifs : Gandhi’s concept of his own religious identity; his provocative non-violence; and his methodology for interfaith conflict resolution. Three scenes from the movie can serve to illustrate the motifs. Provocative non-violence is depicted in the Salt Satyagraha; his methodology for interfaith conflict resolution is depicted in his fast and bedside instruction during the Calcutta riots; and his profession of religious identity is depicted in a statement made from a car to an angry mob outside his ashram, his base of operations near Ahmedabad.

Gandhi was born into Hinduism, but rejected injustices clinging to the caste system. He upheld Hindu-Muslim harmony in the Independence struggle. He steeped himself in the holy books of the great faiths, like the Bible, the Koran and the Bhagavad Gita. He drew on the principles of Jainism, a prominent religious tradition in his native Gujurat. Two of those principles were Ahimsa, meaning non-violence or harmlessness, and Satyagraha, steadfast insistence on the truth.

Gandhi’s sense of his inclusive religious identity is captured in a phrase when driving out to an interreligious political negotiation. He addresses an angry mob of extreme Hindu nationalists (one of whom will become his assassin) who feel that he has betrayed his own. Gandhi says “I am a Muslim and a Hindu and a Christian and a Jew...” Whilst recognising the universalist sentiment in the statement, I think a better formulation that does no violence to his particularism would be along these lines : “I am a Hindu, but that does not mean that I am not a Muslim or a Christian or a Jew etc.”

Such a formulation of identity acknowledges belonging to some definite faith without disidentifying from the other faiths.

Gandhi, like social reformers before and after, attracted deadly violence to himself. Jesus did this, as his religious identity became ambiguous in the eyes of the Jewish authorities. Martin Luther King, inspired by Gandhi, also trod the path of non-violent disobedience, in the American Civil Rights Movement. He was a Baptist who, framing it in the negative, said he was neither Republican nor Democrat. Misperceptions around a peaceful hero’s identity galvanise a violent opposition. Martyrs inspire some and depress others who fixate on the fact that another good person got killed because they were good.

The film explores the provocative nature of non-violent civil disobedience. Gandhi led the Salt March to Dandi on the Arabian Sea, deliberately to break the British law that prevented Indians making and selling their own salt without paying tax. On the walk, he tells the reporter Walker (Martin Sheen) that the authorities are not in control, he is. He initiated the use of spiritual force - Satyagraha, “truth-force”. This was perceived as an attack, and the British retaliated brutally. Shortly following, the waves of Indians marching non-violently towards lines of clobbering police at the Dharasana salt works really concretises the theme. A disturbed Walker reports to the global media that the West lost its moral ascendance on that day. Powerful stuff.

I invite the reader to consider whether or not it violates civilised norms to initiate the use of spiritual and moral force in peaceful protest, though it may attract a physically violent response and court martyrdom. The progressive impulse in humanity seeks to reform the status quo; the conservative to maintain order. Revolutionaries of genius set their sights on a higher order after the conflict has been enjoined. They grasp the paradox of attaining a profounder harmony by pushing through the fire of conflict. This could apply

both to the non-violent as well as the military revolutionary, who more obviously lives and dies by the sword.

Consider the modus operandi for achieving interfaith ends through the sequence depicting the Gandhi’s fast for peace during the bloody riots in Calcutta. Almost expired on a rooftop bed, he demands proof that the Muslim and Hindu combatants have renounced their killings before he will end one of his many protest fasts. His fasts are undertaken as a pennance for any upset and violent reactions his initiatives have unleashed. These mortify the body and deny outlet to personal desire which inflames situations, while the Will of God is more deeply discerned. It is a Jesus-like assumption of responsibility for the sins which technically belong to others.

A tortured Hindu man whose boy was killed by Muslims and who fatally smashed a Muslim boy’s head in return, throws down his knife and tosses a knob of bread on Gandhi’s bed, declaring “I’m going to Hell, I don’t want your death on my soul as well.” Having pointed out that only God knows who goes to Hell, Gandhi tells the man that he knows a way out of Hell. The man is to find a boy of about the same age and size; raise him as his own; but making sure the boy is a Muslim and continues to be raised as such. As the truth of this pathway of reconciliation dawns in the man’s eyes, he breaks down sobbing at Gandhi’s feet. In this peak cinematic moment, Gandhi, brilliantly played by Ben Kingsley, is transfigured in a tender priestly light, prescribing the precise pennance that can justify the human soul to its Maker.

I recommend “Gandhi” as a treasure-trove of themes for interfaith ponderings.

copyright Thomas Kadmon